Criminal defense is unprepared for A.I.

I worked at the Suffolk County District Attorney's Office in Boston when, in 2019, prosecutors who cracked the Golden State Killer case presented their work at the Massachusetts Prosecutors conference. They told a story about uploading crime scene DNA to GEDmatch, an open genealogy platform where people voluntarily share genetic information. The audience was impressed. But they weren't telling the whole story.

What the prosecutors left out: investigators had secretly searched private DNA databases like FamilyTreeDNA and MyHeritage without warrants. They created fake accounts to access people's genetic data, directly violating these companies' privacy policies. A prosecutor later admitted this created a "false impression" of how the case was solved. Even defense attorneys were kept in the dark.

For Americans of European descent, there's now a 60% chance they have a third cousin or closer in these databases; for someone of sub-Saharan African ancestry, about 40%. This isn't innovative detective work. It's a surveillance network built on recreational ancestry testing.

At the recent National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL) Forensic Science and Technology Seminar, what became clear wasn't just the technical capabilities of these AI systems, but who profits from them and who bears the costs when they fail. We're watching powerful technology deployed without transparency, oversight, or informed consent.

Follow the Money

Over 60% of law enforcement agencies now claim to use AI in investigations. The global AI market hit $279 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach $3.68 trillion by 2034. What drives that growth? Data. Every police encounter, court case, and correctional decision generates training data that feeds these markets.

When criminal justice systems deploy AI, three things happen at once:

- The system performs its stated function (identifying people, predicting risk)

- It collects training data that improves the underlying models3. It creates economic value for the companies that built it

This creates a perverse cycle: the more these systems get used, the more valuable they become as products, even when they make mistakes. Companies benefit from wide deployment regardless of accuracy. They have every incentive to expand use, not to ensure it works.

People processed through these systems contribute to datasets worth billions. They bear the costs of errors. They receive none of the economic benefits.

Companies like Clearview AI built their databases by scraping photos from social media platforms in violation of those platforms' terms of service. Then they dismiss concerns about facial recognition as "myths" while selling the technology to police departments. When law enforcement deploys facial recognition, they contribute thousands of facial images daily that refine algorithmic accuracy, typically without data sharing agreements or compensation in place.

Taxpayer-funded activities generate high-quality training data that improves proprietary AI systems. The economic benefits flow almost exclusively to private vendors who own the enhanced models.

Real Harm from Flawed Tech

At Professor Maneka Sinha's session on "Challenging Automated Suspicion," one attorney described how her client was detained for hours because a facial recognition system wrongly matched him to a robbery suspect. The system was confident. The system was wrong. Her client was a young Black man with no criminal record.

- Randal Reid spent six days in jail after facial recognition wrongly matched him to a theft suspect in Louisiana, a state he had never visited. "I have never been to Louisiana a day in my life," Reid said. "Then they told me it was for theft. So not only have I not been to Louisiana, I also don't steal." The detective didn't conduct even a basic search into Reid, which would have revealed he was in Georgia when the theft occurred. The warrant was only rescinded when differences like a mole on Reid's face were noticed. His attorney estimated a 40-pound difference between Reid and the actual suspect. Reid later settled for $200,000.

- Bobby Jones, then 16, was detained based on a predictive policing program that flagged him as "high-risk" without him or his parents knowing.

- Pasco County's program used school records to flag children as "potential criminals," subjecting families to intrusive surveillance.

- Ms. Gonzalez and her 12-year-old sister were detained at gunpoint after an automated license plate reader misread a single digit on their plate.

In each case, technology outputs became the sole justification for police action. No traditional investigation. No human judgment. Just an algorithm saying so. Meanwhile, each interaction generated more data, improving the systems and increasing their economic value, even while producing harmful errors.

AI changes how people become suspects through what Professor Sinha calls "automated suspicion" in her Emory Law Journal paper. Imagine being stopped by police not because of anything you did, but because a predictive algorithm flagged your neighborhood as a "likely" crime area. Or being arrested because facial recognition wrongly matched your face to a suspect photo. Technologies like predictive policing, facial recognition, and automated gunshot detection now make decisions once made by trained officers. They claim to predict where crime might happen, who might be involved, or whether a crime occurred, through processes too opaque for most officers to understand.

Automation bias (our tendency to trust machines) and confirmation bias (our tendency to seek evidence that confirms what we already believe) lead officers to accept algorithm outputs as gospel. Courts typically defer to police judgments about "reasonable suspicion" or "probable cause," and now extend that deference to technology without assessing whether the technology is reliable. As Professor Sinha notes, courts often treat algorithm outputs as objective facts rather than probabilistic estimates requiring scrutiny.

The Technologies

Facial recognition is broken, but profitable.

Facial recognition claims accuracy rates above 97% in controlled settings. Real-world conditions tell a different story. A 2023 GAO report found only three of seven federal law enforcement agencies had policies protecting civil rights when using facial recognition. These systems show higher error rates when identifying people with darker skin tones. Numerous studies confirm the technology performs worse on people of color and women compared to white men. A national study found that agencies using facial recognition had a 55% higher arrest rate for Black people and a 22% lower arrest rate for white people, compared to agencies that did not use the technology.

As of 2023, some agencies had conducted tens of thousands of searches with no training requirements in place. Companies that combine different biometric data (like face and voice together) gain massive advantages over competitors. Research shows that combining face and voice recognition is 100 times more powerful than using face recognition alone. This multiplication effect creates a "race to be first" mentality. Just like pharmaceutical companies might compete to rush a drug to market first, companies rush AI systems into use before proper validation. When being first means capturing most of the market, speed beats safety.

Tax incentives make AI artificially cheap. Research shows companies pay lower taxes on machines than on workers. This creates financial pressure to deploy systems before proper testing.

Predictive Policing

Predictive policing tools analyze historical crime data to forecast hotspots or flag "at-risk" individuals. The problem: most of that data comes from police operations themselves. The NACDL report "Garbage In, Gospel Out" shows how these systems, trained on biased historical patterns, create self-fulfilling prophecies. Police patrol more heavily in neighborhoods the algorithm flags. More policing generates more arrests. More arrests "prove" the algorithm was right.

Even when using victim report data, supposedly less biased than arrest data, predictive algorithms still disproportionately label Black neighborhoods as crime hotspots. Reporting itself reflects racial dynamics: wealthier white people are more likely to report crimes supposedly committed by Black individuals.

Cell Site Location Data

Police officers with basic FBI CAST training often testify that cell phones can be precisely tracked using cell towers. They claim towers have neat, predictable coverage areas reaching exactly 4-5 miles, with phones connecting to the closest tower 70% of the time. This makes it seem like they can pinpoint someone's location with high confidence.

The reality: radio frequency propagation depends on frequency (lower frequencies travel further), terrain, building materials, weather, network load, and network protocols like "cell selection hysteresis" (which prevents phones from rapidly switching between towers in overlapping coverage areas). These simplified models presented by FBI CAST-trained officers grossly misrepresent the complex physics involved. Accurate analysis requires data often withheld (like frequency bands used) and expertise far beyond a two-day training course. Defense attorneys can challenge these oversimplified models under evidence standards like Daubert or Frye.

Probabilistic DNA Analysis

Tools like STRmix and TrueAllele analyze complex DNA mixtures where multiple people's DNA appears in a single sample. Their "black box" nature, combined with companies' refusal to disclose source code (citing trade secrets), makes challenging their reliability difficult.

In practice, this means defense attorneys often can't access the actual code that determined their client was "a match" to DNA found at a crime scene. Imagine being told "our proprietary algorithm determined you were at the crime scene with 99.9% certainty" but not being allowed to examine how that determination was made.

This is what economists call "vertical integration" in the AI value chain: companies control both the data collection and the analysis, creating high barriers to transparency and accountability. These companies' business models depend on maintaining proprietary control over their algorithms, creating direct conflicts with defendants' rights to examine evidence against them.

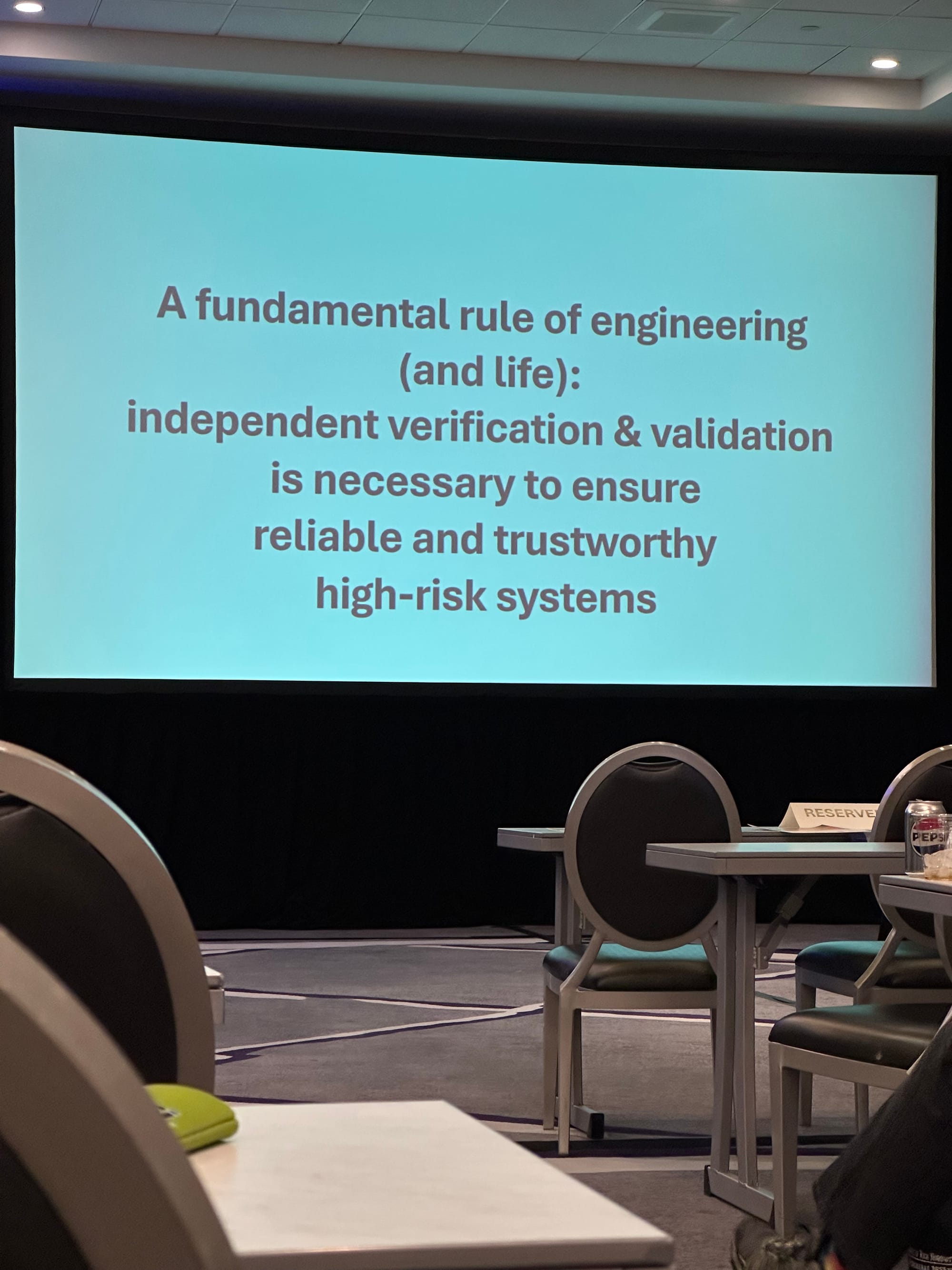

In State v. Pickett (2021), a New Jersey appellate court recognized the defendant's right to examine the software's source code. The court held that when the state uses "novel probabilistic genotyping software" to give DNA testimony, a defendant can access the source code to challenge its reliability. The court noted: "Without access to the source code, the raw materials of the software programming, a defendant's right to present a complete defense may be substantially compromised." Independent analysts reviewing STRmix discovered the program produced false results in 60 cases. There's no reason to assume proprietary systems are immune from similar errors.

Large Language Models in Court

LLMs fabricate information. In Mata v. Avianca, a lawyer submitted fictional case citations generated by ChatGPT, resulting in sanctions and judicial warnings that rippled through the legal profession.

This problem has only gotten worse. In February 2025, a Wyoming federal judge sanctioned lawyers from Morgan & Morgan, America's largest personal injury firm, for submitting filings with eight fabricated cases from their in-house AI platform. The attorney had used the firm's platform, MX2.law, uploaded a draft, and asked it to "add to this Motion in Limine Federal Case law from Wyoming." Without verifying the citations, he included them in the filings. The lead attorney had his pro hac vice status revoked and was fined $3,000. Morgan & Morgan called it "a cautionary tale for our firm and all firms."

Similarly, in late 2024, Judge Marcia Crose in the Eastern District of Texas sanctioned an attorney who submitted a response to a summary judgment motion containing nonexistent cases and fabricated quotations generated by AI. The court imposed a $2,000 penalty and ordered the lawyer to attend continuing education on AI in legal practice.

A May 2024 Stanford study found legal AI tools produce incorrect information in about one of every six queries. As of late 2024, more than 25 federal judges have issued standing orders requiring attorneys to disclose or monitor AI use in their courtrooms. Lawyers cannot delegate their duty to verify.

Courts are Catching Up

Government agencies have evolved beyond regulatory functions into active participants in AI data economies. In criminal justice, agencies simultaneously purchase AI systems while generating the very data that makes these systems valuable. These public-private partnerships create massive one-way data transfers. Taxpayer-funded activities generate high-quality training data that improves proprietary AI systems, yet the economic benefits flow almost exclusively to private vendors who retain ownership of the enhanced models.

Professional organizations are issuing guidance:

- ABA Resolution 604 provides guidelines for AI use by legal professionals-

- Florida Bar Ethics Opinion 24-1 addresses confidentiality and competence issues

- NYC Bar Association Formal Opinion 2024-5 emphasizes that lawyers need "guardrails and not hard-and-fast restrictions"

But courts rarely understand the economic incentives shaping these technologies. When a company's business model depends on maintaining proprietary control over algorithms used in criminal cases, this creates fundamental tensions with due process rights.

State v. Loomis raised concerns about proprietary risk assessment algorithms that defendants couldn't examine. While upholding the sentence, the court noted serious concerns about such tools, setting the stage for stronger challenges.

Professor Sonia Gipson Rankin warns against AI becoming "automated stategraft," systems that, under the guise of neutrality, extract resources from specific communities. Her research shows how automated traffic enforcement cameras generate revenue while disproportionately impacting low-income communities, often without demonstrable safety benefits. Communities subjected to increased surveillance are unwittingly contributing valuable training data that improves systems and increases market value, while receiving none of the economic benefits.