Mauna Loa, Climate Science's North Star

When you grow up about as far as you can from the middle of the Pacific, you're socialized to understand it as a place of potential leisure, rather than someone's home. I fell in love with the Big Island of Hawai'i, but I continue to curse myself for how little I knew about its exploitation.

Take a moment to think about what you know about Hawai'i. What do you know about the man who supposedly "discovered" it, Captain James Cook?

A Short Recap of Enlightenment Sciences

Captain Cook lived and breathed during the heyday of the European Enlightenment. In 1660, the Royal Society was founded in London and received its royal charter from King Charles II two years later. A little over a century after that, in 1769, the ambitious young Captain Cook was commissioned to journey to the middle of the Pacific, to Tahiti, to observe the transit of Venus.

Enlightenment astronomers understood that Venus could help them measure the scale of the solar system. Edmund Halley (namesake of the famous comet you can next see on July 28, 2061) explained as much in 1716. Venus occasionally crosses the Sun's face, visible from Earth as a jet-black disk drifting slowly among the Sun's real sunspots. Halley reasoned that by observing the transit times from different locations on Earth, astronomers could determine the distance to Venus using parallax. The rest of the solar system's scale would follow.

"But after all the only conclusion they made was that as we had so much to do with the sun and the rest of the planets whose motions we were constantly watching by day and night, and which we had informed them we were guided by on the ocean, we must either have come from thence, or be some other way particularly connected with those objects..."

~ John Ledyard, Journal of Captain Cook’s Last Voyage

Halley was following the work of astronomer Giovanni Cassini. Between 1671 and 1673, Cassini used parallax to determine the distance to Mars by coordinating observations from Paris with measurements taken by his colleague Jean Richer in French Guiana. He could compute the distance because he knew the baseline: the distance between the two observers. Cassini then used Kepler's orbital mechanics to calculate the distance from Earth to the Sun. But even then, neither he nor his successors could pin down the true size of the solar system.

The size of the solar system remained one of the central mysteries of 18th century science. Astronomers at the time knew the Sun was orbited by six planets. Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto had yet to be found. They knew the relative distances between planets, but the absolute measurements remained unknown.

Venus crossing the Sun is rare. In our lifetimes, it happened in 2004 and again in 2012. It won't happen again until 2117. Halley knew in the early 18th century that he would not live 60 years to see the next one. The task fell to Captain Cook.

Cook reached Tahiti eight months after setting sail from Plymouth in August 1768, navigating the HMS Endeavour around Cape Horn. He was not alone in the effort; over 150 individuals journeyed to far regions of the world to prepare for the astronomical event.

Here lies the problem: most locations these expeditions "visited" were already inhabited by indigenous peoples who had little contact with European colonial empires. This is where Enlightenment science and colonial conquest become entangled. Captain Cook and his crew of nearly one hundred officers, marines, and civilians made many stops on the way to and from Tahiti, claiming Pacific lands for the British Empire regardless of who already lived there. The islands of Hawai'i were among them.

Discovering what, exactly?

In the West, the period from the 1400s until about the 1700s CE is usually called the "Age of Discovery." The term implies that the history of the Americas, or the "discovered world," didn't exist until European contact. In 1935, legal scholar von der Heydte wrote about this problem when analyzing the Falkland Islands dispute:

The problem we have to deal with...cannot be characterized by the opposition of the two notions of "discovery" and "possession" under such a general conception as "acquisition of sovereign rights," but by opposition of "symbolic annexation," on the one hand, and "effective occupation" on the other, under the general title "possession." ~ von der Heydte, 1935

In other words, a sighting or "discovery" might confer rights, but occupation was what transferred land to imperial ownership. Native rights were irrelevant.

Charles C. Mann explains it well: in the colonizer's eyes, Native populations lived in an eternal, unhistorical state. This is sometimes called "Holmberg's Mistake"—a strange term that implies these actions were accidental, as if that could excuse genocide, slavery, and the ongoing occupation of Native Hawaiian homelands. The logic runs: discovery produces change, change creates history, and these people are eternal, without history. A fallacy.

Contemporary Occupation, and Science

By the 19th and 20th centuries, these European land claims became the foundation for westward "expansion" in the United States. Once independent, America began building the legal basis for its own territorial growth.

The first major case was Johnson v. McIntosh, 21 U.S. 543 (1823). The Supreme Court held unanimously that Native Americans do not own the land they live on, ruling that "the principle of discovery gave European nations an absolute right to New World lands."

The facts: members of the Illinois and Piankeshaw tribes sold land to Thomas Johnson in the 1770s in what is now Illinois. After American independence, the tribes sold the same territory to the federal government, which then sold it to William McIntosh. The Court ruled for McIntosh. This case introduced the Doctrine of Discovery into American law and established federal dominance over Native affairs.

Two subsequent cases—Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832)—completed what's called the "Marshall Trilogy." Together, these three rulings laid the groundwork for Native American forced removal, including the Trail of Tears, and provided legal cover for stripping Native people from their homelands. This was the framework under which the occupation of Hawai'i was later justified.

By the mid-1800s, American law permitted colonists to remove Native Americans from their homelands and claim ownership. The term "Manifest Destiny" first appeared in 1845 as philosophical justification for American expansion.

The reasons for "discovery" were often described as divine or resource-driven. What's often erased is how science developed hand-in-hand with imperialism. I believe in looking to the stars, but I wish we did so with more awareness that the settler colonial state has expanded alongside astronomical science. Western space science remains bound up with settler colonialism.

The Present Day

2022 marks 244 years since Captain Cook became the first European to visit Oahu in January 1778. It also marks 124 years since the United States annexed the then-sovereign nation of Hawai'i in 1898, after American sugar plantation owners and other agents overthrew Queen Liliʻuokalani in January 1893. The path to truth and reconciliation is not simple—just as it's nearly impossible for the international scientific community to find another mountain so remote from light pollution and so high up with such thin atmosphere from which to observe the stars.

The Mauna Kea Observatories conduct major astronomical research and make science more accessible to students from nearby University of Hawai'i at Hilo. Since 1958, researchers have taken air samples at the Mauna Loa Observatory, making it one of the most important sites for climate science.

Charles Keeling established this framework for modern climate research just as Hawaii was about to become a U.S. state. Monitoring at Mauna Loa produced groundbreaking results within months of starting. When Keeling first climbed the volcano in November 1958, he found that carbon dioxide concentration was gradually but steadily rising. Then, through the summer, CO2 levels dropped. The pattern repeated the following year. Keeling found it intriguing.

In his autobiography, Keeling noted: "we were witnessing for the first time nature's withdrawing CO2 from the air for plant growth during the summer and returning it each succeeding winter." They had recorded how the northern hemisphere breathes—releasing carbon dioxide when forests lose their leaves in winter, inhaling as leaves return each summer.

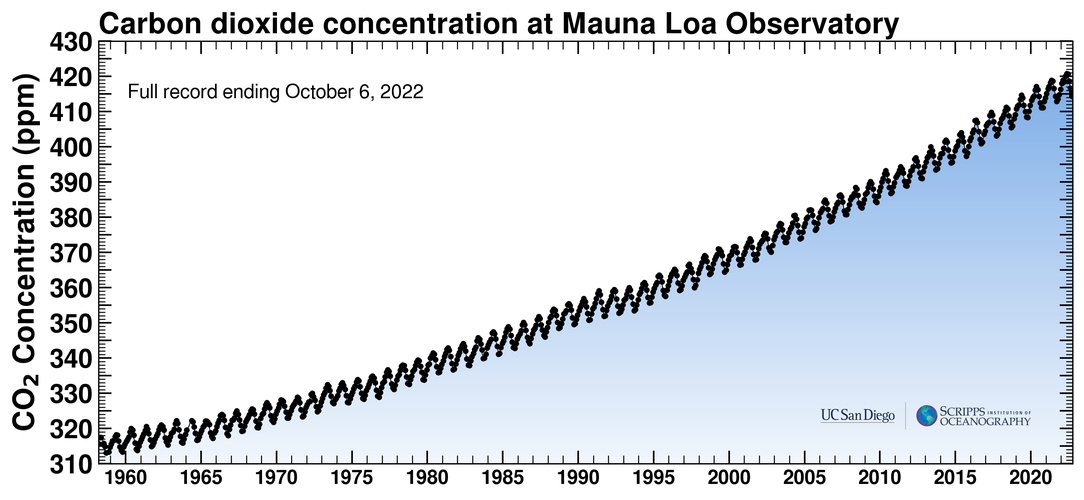

The regular measurements supported a hypothesis that atmospheric carbon was rising year over year due to growing global population and industrialization. Keeling compiled these measurements into a graph with an upward trend he called the "[Keeling Curve](https://keelingcurve.ucsd.edu/)." The Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego updates it daily. You'll find it referenced at every United Nations Climate Change Conference.

The seasonal breathing of CO2 was just one of Mauna Loa's revelations. Over the following 60 years, the observatory documented something far more alarming: a sharp rise in carbon dioxide levels driven by fossil fuel combustion.

NOAA and Scripps researchers take great pains to ensure their findings are unimpeachable. Climate science has been one of the most contested issues in American politics since Keeling first presented his results to the American Philosophical Society in 1968. According to Monmouth University polling from 2021, roughly one in four Americans did not believe climate change was happening at that time.

Friends posing for stars atop Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa. Photos by me.

As countries pursue decarbonization and try to curb greenhouse gas emissions, Mauna Loa Observatory must remain an unimpeachable pillar of truth in the fight against climate crisis. I wish the now conveniently apolitical science could find a way toward truth and reconciliation with the painful history on which the observatories on Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea sit.

I don't have an answer for how truth and reconciliation should begin. But perhaps one could do as I have: take the time to listen to Native Hawaiians, who have shared plenty about their own experiences, as long as you're listening.