Where There Is Nothing

Flying into Windhoek, Namibia, you're greeted with a window view of sweeping sand dunes as far as you can see, hardly a cloud in sight. The experience doesn't stop there—you're also met with turbulent winds that made for one of the most stressful landings I've ever experienced.

Namibia is beautiful, known mainly for its namesake, the Namib desert. The name "namib" comes from the Nama language, implying “an area where there is nothing.” Ironically, it is in nothing that the most wonderous something can be found. This is where my journey began, on an eleven person group tour with Chameleon Safaris in Windhoek, that would span 7 days and 2,500 kilometers across the country.

Day zero, the arrival

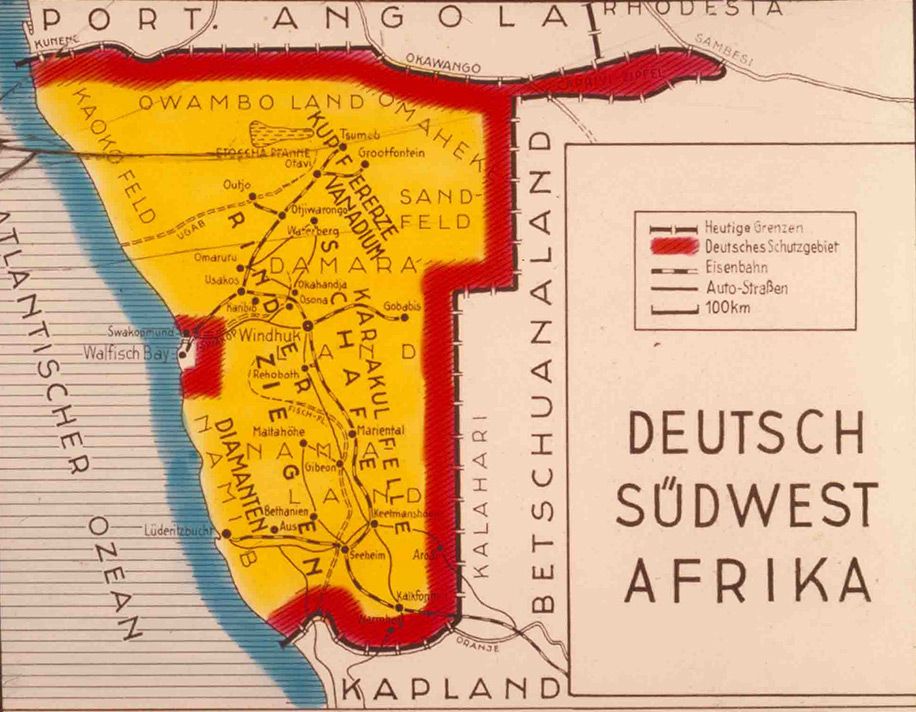

After getting to my hostel, Chameleon Backpackers (also run by the safari company), I realized that aside from the famous photos and videos of sweeping sand dunes, I actually knew next to nothing about the former Imperial German colony, once known as German South West Africa.

I was surprised, then, to learn that North Korea would be the gateway to understanding Namibia's history in person. The Independence Memorial Museum, dedicated to Namibia's anti-colonial resistance and national liberation movement, was designed and constructed by Mansudae Overseas Projects, a North Korean firm that builds projects in foreign countries using North Korean designers and socialist realist design patterns.

Critically acclaimed podcast "99% Invisible" has an entire episode dediated to this structure, and the diplomacy efforts of North Korea through the construction of overseas monuments.

I had never seen anything North Korean with my own eyes before, so my curiosity was immediately piqued. The run-down symmetrical architecture looked mesmerizing yet out of place in central Windhoek. Underneath the building, you find the entrance to the museum. You'll also find three murals above the doorways on each of the foundational columns, depicting the struggle for independence.

Knowing the North Korean context taints the experience a little, I must admit. You're simultaneously aware that the stories depicted are those of the Namibian peoples' fight against German, English, and later Apartheid South African occupation, but also a platform for North Korea to tacitly express disdain for the colonial powers of old. Clever game they play. I snapped some photos.

I returned to my hostel and attempted to get some rest before the first day of the safari.

Days One and Two: The "Roads" Less Traveled

Aside from a few central arteries, most of the ways you drive around Namibia are graded dirt roads. Driving is the only way around—there is no public transportation. If you're driving yourself, opt for the 4x4 rental vehicle. The suspension and undercarriage of your 2WD rental sedan will get absolutely wrecked.

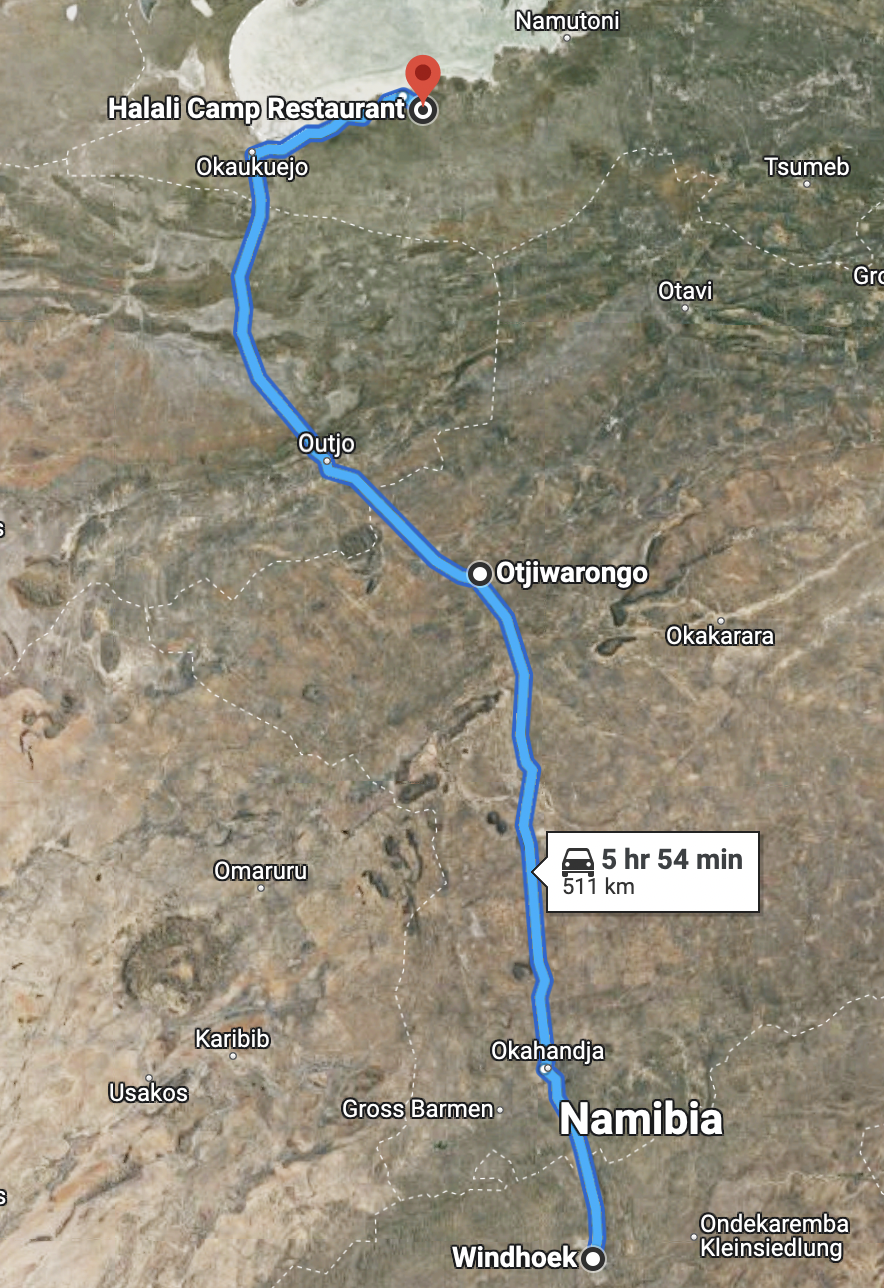

We started our day driving up to Otjiwarongo, stopping for supplies and a tiny lunch, before continuing onward to Etosha National Park.

Etosha National Park is known for its great game viewing opportunities, particularly at the many waterholes found throughout the park. During the dry winter months, many species rely on these permanent water sources. Visitors can see large groups of zebra and springbok mingling with oryx and bathing elephants at the larger waterholes. Some camps even offer floodlit waterholes where you can spot rhino, elephant, and lion drinking from the same spot.

Etosha is home to four of the "Big 5": elephants, lions, leopards, and rhinos. (The fifth, the Cape buffalo, prefers wetter habitats and isn't found here.) The park also features rare and endangered species such as the black-faced impala and the cheetah. The vast Etosha Pan, a large dried-up salt pan, provides a stark backdrop for game viewing.

Unfortunately for us, we visited in Summer, when rainfall is abundant in northern Namibia and animals are reluctant to visit watering holes. This makes game viewing challenging, but we still spotted some from our vehicle.

Some of the wildlife we were able to view from the safari vehicle that took us all across Namibia. The roof of the vehicle popped up, allowing us to stand on our seats for a better view. All photos by me.

Days Three and Four: The Enormity of Nothing

In a 2016 essay for The New York Times, my cousin Sarah Khan wrote that "Namibian soil is the souvenir that reappears when you least expect it, bringing with it a sand storm of memories." I probably found it in every crack and crevice of my technology and belongings for a week and a half after I left Namibia.

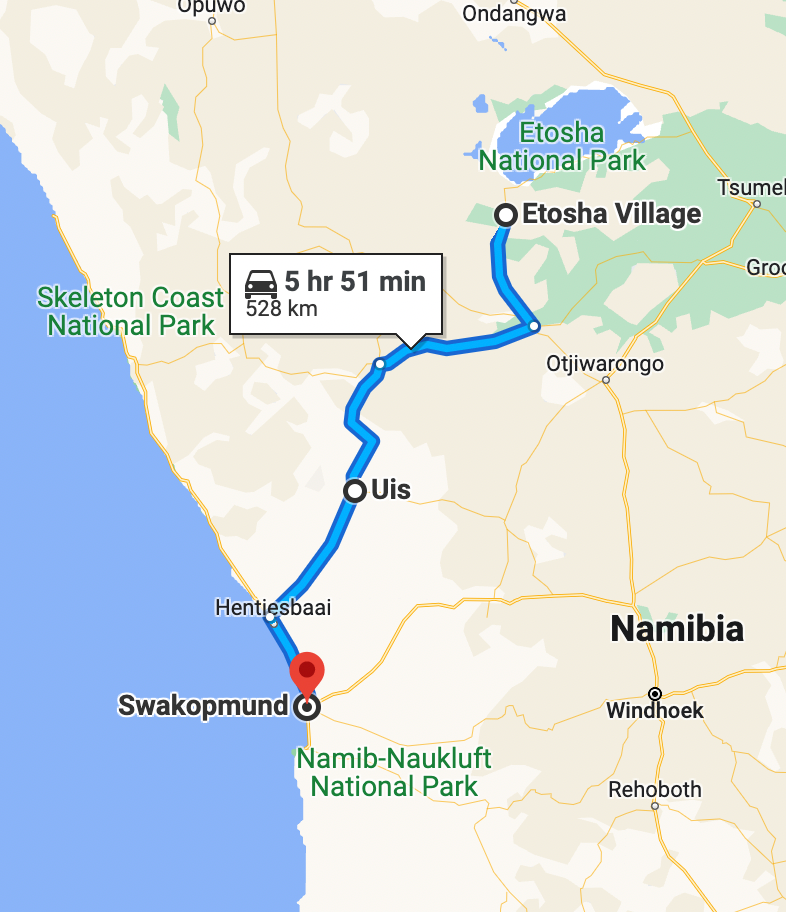

We began our trek into the desert by heading southwest from Etosha, making curated stops along the way to visit Native Damara, Kavango, Tswana, Herero, and Himba people.

Admittedly, I am not a huge fan of "Native-gazing" activities that tourists partake in during their visit to Africa—it feels both reinforcing of white supremacy, and also of the post-colonial economic destitution that colonial institutions placed on Natives who weren't allowed self-determination. Therefore I will not be sharing any photos of those moments that I reluctantly experienced.

Instead, I'll share a little about the Herero people and these beautiful dolls I found that they make and sell as a tourist commodity.

A Brief History of German South West Africa

The colonization of Namibia by the Germans began in the late 19th century. In 1884, the German Empire claimed the territory as a protectorate and established the colony of German South West Africa. The German government encouraged settlement by Germans and sent thousands of farmers and merchants to the colony. They brought new technology and infrastructure—railroads and telegraph lines—but also imposed their culture and laws on the indigenous people.

The German colonial administration implemented racist policies. The indigenous people, particularly the Herero and Nama, were subjected to forced labor, dispossession of their lands, and suppression of their culture. They promoted German as the official language and suppressed local languages. The legacy of this remains visible today.

Sexualization towards domestication

In Damaraland, German settlers acquired land from the Herero to establish farms that they then hired Herero people to work on. At that time, our guide explained, the Herero dressed as the Himba continue to do today, with garments covering lower genitalia for both sexes and leaving breasts exposed for women.

In Western societies, the objectification and sexualization of women has been perpetuated by media, advertising, and power dynamics. In contrast, many traditional cultures, such as the Himba, have different attitudes towards nudity. For the Himba, exposed breasts signal maturity and are not considered sexual. The Himba have a different understanding of modesty and the human body than Western societies do.

When these factors clash in tourism, you find that visitors may view the nudity and traditional customs of the Himba as unique and intriguing—something different from their own culture. But the Himba's nudity should not be objectified. It's part of their culture and way of life, not entertainment or spectacle.

The Herero once dressed as the Himba do now, but no longer. German colonizers forced the Herero people to wear Victorian-style clothing, including long dresses, petticoats, and Victorian hats. This was a way for the colonizers to assert dominance over the Herero. They were forced to wear these clothes as part of being "civilized" into German society, and so they could eventually be domesticated for the colonial labor force.

The Herero and Nama genocide, the first genocide of the 20th century, was a consequence of tensions brought on by German colonization. Between 65,000 and 100,000 Herero and Nama died as a result of starvation, imprisonment, and concentration camps set up by the German Empire to confine them in the Namib desert.

The Herero genocide remains a tragic reminder of the devastating consequences of colonialism and the belief in racial superiority.

At nightfall, we arrived in Swakopmund, a beautiful German colonial city established in 1892.

On the agenda was dinner and rest, before we set off the next morning to witness one of the great wonders of southern Africa.

Satellite visual of the area just south of Swakopmund. The sweeping area known as Sandwich Harbour begins just after Walvis Bay. The Sand dunes stretch for hundreds of miles, taking on a red hue the further south you go.

Meet Me Where the Sand Meets the Ocean

Just south of Walvis Bay, at the edge of the South Atlantic Ocean, is Sandwich Harbour.

The ocean crashes into dunes that rise hundreds of feet. Orange sand, blue water, empty sky—I kept looking around trying to understand what I was seeing. The silence was the strange part. No birds, no traffic, just wind and the occasional wave breaking. Everything felt oversized and slightly unreal, like standing inside a photograph.

What surprised me most was that people drive on this. A new guide met us in Swakopmund and had five of us pile into his tiny 7-seater 4x4 SUV.

Sweeping view of the sand dunes as a sight in of itself, but moving across it at a blistering speed with the vehicle we were in was an added delight. The photo of the vehicle was taken on a Fuji GA645Zi camera with Kodak Gold 200 film.

We made many stops in Sandwich Harbour to find new vantages. It was here that I learned the trick of digging your bare feet about 4 inches into the sand to keep them cool—the scorching heat was otherwise unbearable.

It really is good that the ocean is there, because if not for it I am certain our driver would have been lost.

Unfortunately, I wasn't careful enough with the Fuji, and there is sand in the device. I'm hopeful I can use some industrial strength compressed air to remove it, but until then the camera is "beached."

⚠️ Make sure that the equipment you bring is at least weather-sealed, and even that may not be enough! ⚠️

Days Five and Six: There Is Always More Sand

After our adventure-filled morning in Sandwich Harbour, we made the journey across the Namib desert to Desert Camp, just outside Sesriem, Namibia. The 300km journey had us passing through the Tropic of Capricorn, where we stopped for photos.

Desert Camp is located just outside the entrance to Sossusvlei. It's simple but comfortable, with great views at sunset. If you're luckier than I was, stay there during the new moon so the night sky stuns you with stars.

The next morning was day five. We departed before sunrise at about 5am to beat the queue into the National Park and were rewarded with beautiful sunrise views of the landscape before us.

Documenting the journey into Sossusvlei, Namibia. Our destination is to view the golden red sand dunes that tower over the roads.

The Postcard Is Real

After a brief 45-minute drive into the park, we made our first stop

An oryx antelope grazing near dunes that people are boldly climbing. Sand is incredibly difficult to climb, I've learned.

You've seen these dunes on desktop wallpapers and in travel magazines. I had too, for years. Standing in front of them, I kept thinking: so this is what that looks like in person. The red-orange sand against the blue sky is exactly as saturated as the photos suggest. These dunes are some of the tallest in the world, and the wind has been shaping them for millions of years. Each ridge casts a hard shadow in the morning light.

As you stand in the middle of it, the scale doesn't quite register. The dunes go on in every direction, shifting color as the sun moves.

These are the dunes of childhood desktop wallpapers, the ones I imagined when I stared at screensavers, the ones I drew with colored pencils as a kid.

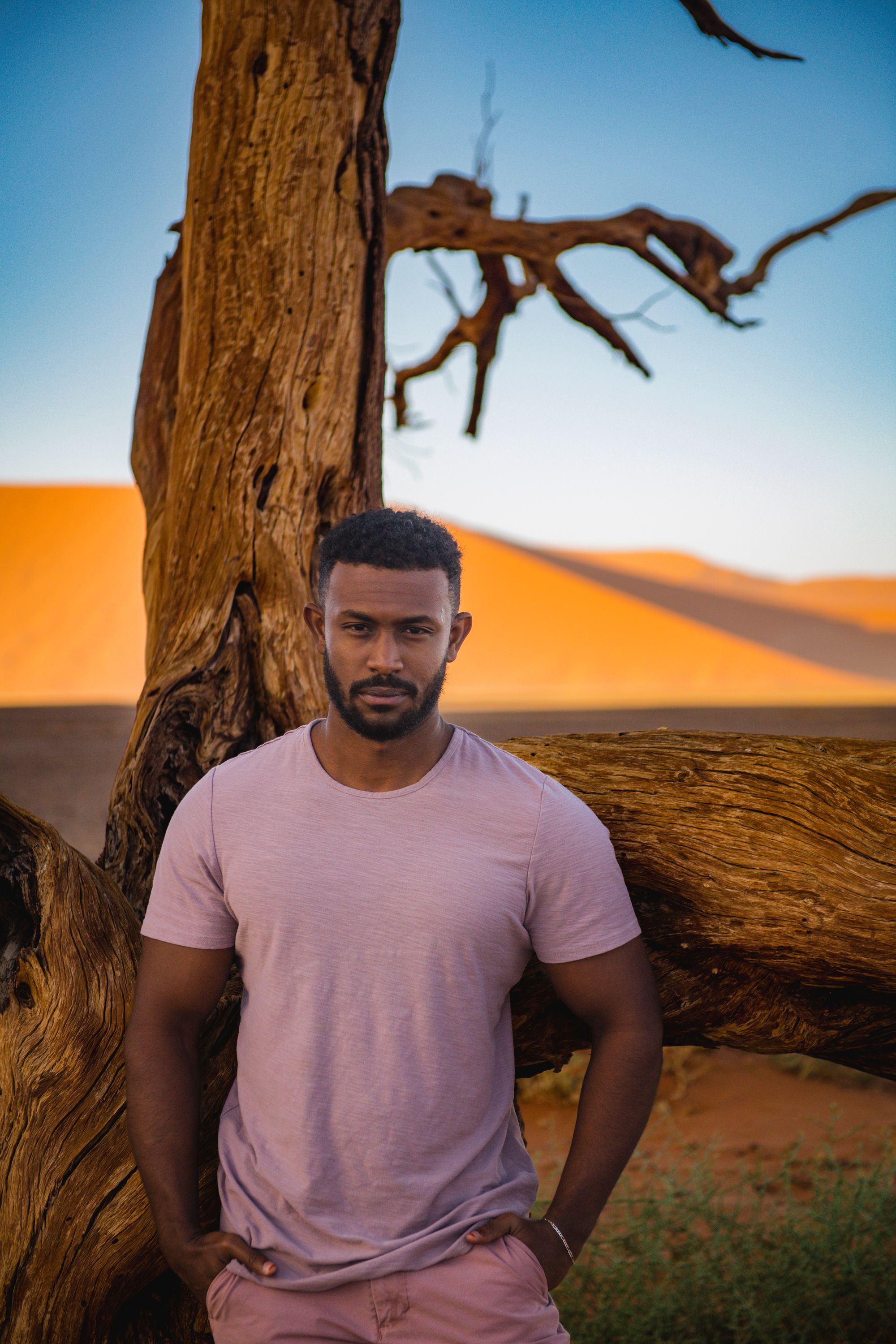

A visit to the sand dunes wouldn't be complete without a photoshoot. Mohammed poses for some portraits in front of a tree of unknowable age.

Our next stop was Deadvlei, the famous clay pan that provides an equally stark contrast to the bright orange dunes of Sossusvlei. The Tsauchab river formed the clay pans after flooding, allowing camel thorn trees to grow. When the climate changed, drought hit the area, and sand dunes blocked the river. The trees died, but because it's too dry for them to decompose, they remain standing in the pan—black against the white clay, estimated to be around 900 years old.

We hiked up a neighboring dune first to have a vantage of the surrounding area, before hopping down into the clay pan.

Be extremely careful with your electronic equipment. I brought a 200-500mm super telephoto lens for dramatic portraiture, and I have to admit I was more than a little nervous each time I swapped lenses.

Photos showing Deadvlei online tend to be heavily edited—while the contrast is stark, the clay pan has an orange-red hue to it, not the near-white that an online image search might lead you to believe.

Wrapping Up an Extraordinary Visit

Namibia is unlike anywhere I've ever visited. And, although I say this about a great many places I have spent time: I would like to go back.

The photographic opportunities are near endless. I think it would be lovely to explore more of the sand in the Winter season and at more dramatic times of day and night. I can only imagine how incredible it would be to spend an evening under the stars in Sossusvlei, or Sandwich Harbour, and take night sky time-lapses of the stars. Even more fun would be to do what Sarah did and road trip in a 4x4 vehicle from Cape Town, allowing more time to explore the areas that stood out to me with all the gear that I can fit into a vehicle.

If you have questions or want advice on your Namibian trip planning, feel free to reach out.

- Windhoek: Avani Windhoek (www.avanihotels.com)

- Etosha: Taleni Etosha Village (www.etosha-village.com)

- Swakopmund: Hotel Pension A La Mer (www.pension-a-la-mer.com)

- Sesriem/Sossusvlei: Desert Camp (desertcamp.com)